Sharing missions stories: Three rules to keep you from falling into the rude foreigner trap

By Anna McShane —

None of us like to be the foreigner. Being foreign means standing on the outside looking in, being different, lacking a sense of belonging. But when we visit a new country, especially if we are a short-term worker or on a vision trip to help our church at home understand where God is calling us to work, we ARE the foreigner. How can we look, learn and share about our experience, and yet not offend?

>> This is part 1 of a two-part series. Read part 1: “Tips to guide careful communication.”

For many years my husband and I were the advance media team that went to new countries to “spy out the land” before SEND placed any long-term workers there. We also lived overseas on two separate occasions, and we currently spend about a quarter of our year doing cross-cultural ministry.

We are Americans, and proud of it. But our culture tends to be loud, brash, in-your-face, and overly friendly. On blogs or social media, we often share quite openly and sometimes quite critically. As we have lived overseas and served in missions through media, we have developed a few guidelines to help us share truthfully, but tactfully.

1. Wait to write.

Take mental notes on what you see and learn, but let it soak in your mind before you dash off a note home or post something on Facebook or publish a blog. In fact, when you are initially visiting a new country, refrain from posting and blogging as much as possible. Let friends at home know you are alive, but forget the daily updates. Put your phone away and immerse yourself in the reality of where you are, not the cyber unreality of where you aren’t. Let’s face it, you don’t know enough yet to write much anyway. One time we did a survey trip to Hong Kong. For three long days I sat in on interviews that our Asia leader did with local leaders, walked the streets, price shopped in the grocery and department stores, asked questions, but wrote nothing. Then, when we left, I wrote like mad.

2. Run everything past your “review board."

Especially when we lived overseas, we had an imaginary review board for everything we wrote or produced. It was made up of a group of people we personally knew. Though none of them ever really did a review, we would think through how they might react to our words before we published. Everyone has their own unique audience, but our imaginary board included:

- A former neighbor who was a strong believer, and also a strong Roman Catholic. During our four-year term in the Philippines, his job was to vet everything we portrayed about Catholicism in that country.

- An elderly auntie who was only familiar with denominational funding of global work. She was there to review whether or not we explained finances in a way that would make sense to someone who wasn’t accustomed to individuals raising their own support.

- A Filipino supporter. His job was to be sure we were gracious and honest about the Philippines.

- An unbelieving former co-worker. She was there to make sure we didn’t get too holier-than-thou in our writing.

- My master’s thesis advisor who is also a Wall Street Journal photographer. His job was quality control. Excellent writing. Excellent pictures. Nothing less.

3. Keep the camera under cover until you’ve settled in.

When you do take your camera out, be very cautious how you shoot. Always ask ahead of time if it is OK to shoot pictures. Ask too if there are particular superstitions about photos – one country we’ve worked in never puts only three people in a picture.

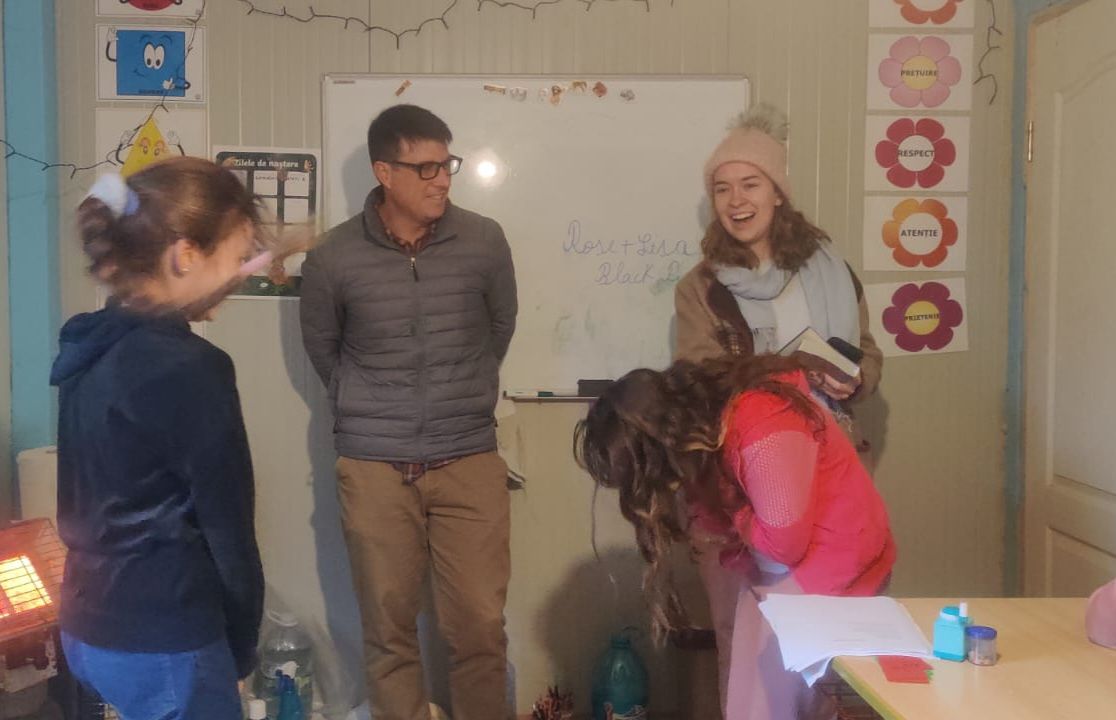

If you are in a busy marketplace or village, find a quiet corner and shoot with a long lens. If you are visiting a church or Bible study, sit for at least 15 minutes before you even take your camera out of the case.

Look at the place you are visiting with the eyes of someone who may live there a long time. Don’t shoot things that would embarrass the local residents. How would you feel if a visitor to your country only photographed the dirt in a slum and ignored all the beauty?

Even in the hard places, look for the faces and souls of real people. I think of the lovely eyes of a little girl sitting in a laundry basket in a Philippine slum while her mother asked us questions, assuming we were Peace Corps workers. Or the wrinkled, smiling face of a Buryat man in Siberia who told us how he had come to faith. Or the smooth cheeks of a sweet teen in a rural village who held out her apple and asked, “Have you eaten?” which I didn’t at that time know was the culturally appropriate way to say good morning.

One day we were walking the dirt streets of a refugee camp in the Balkans. While our local workers introduced us to various men they knew in the camp, my husband slipped off on his own. In the streets of squalor, he made friends with a little boy who took him home. He led my husband into a one-room hut, whitewashed, with a carpet, and a stop-the-camera old woman rocking a baby in a cradle. My husband sat a while, then motioned with his camera, and got her permission to shoot a picture. Beauty, in the midst of poverty.

Additional Posts